After repeated setbacks in China’s job market, a growing number of young Chinese are turning their gaze abroad. Unlike earlier waves dominated by elites, this newer group is more willing to take blue-collar or high-risk assignments, and even to relocate to non-traditional destinations in South America and Africa—anything to secure savings, mobility, and a second chance. Yet the exit routes themselves are tightening: overseas postings have become far more competitive, pay has fallen sharply, and once “always-in-demand” migration occupations are now showing signs of saturation.

“If I don’t leave now, it’ll only get harder”

Xiao Bo has been preparing to emigrate for three years. His working plan is to switch careers and go to Australia as a caregiver; if that fails, he says he may join the French Foreign Legion.

Speaking after finishing work at 11 p.m., he sounded exhausted: “If I don’t leave now, it’ll only get harder in the future.”

Xiao Bo works in recruitment at a Chinese state-owned enterprise. Over the past few years, he has watched hiring shrink again and again—deepening his anxiety about the labor market. A position paying 3,000 to 5,000 yuan a month (about S$450–915), he said, hired 15 people from 400 resumes in 2022; by 2023, it drew 1,000 resumes to select only eight hires.

He summed up what he sees as three options for young people today: “Lie flat, grind, or run. The track for grinding has collapsed, and the track for running is about to collapse too. So I have to speed up and pray I can escape before it collapses.”

With China’s youth unemployment hovering around 17%, many “post-2000s” job seekers like Xiao Bo have begun looking overseas—forming a new wave of would-be emigrants beyond the traditional elite cohort.

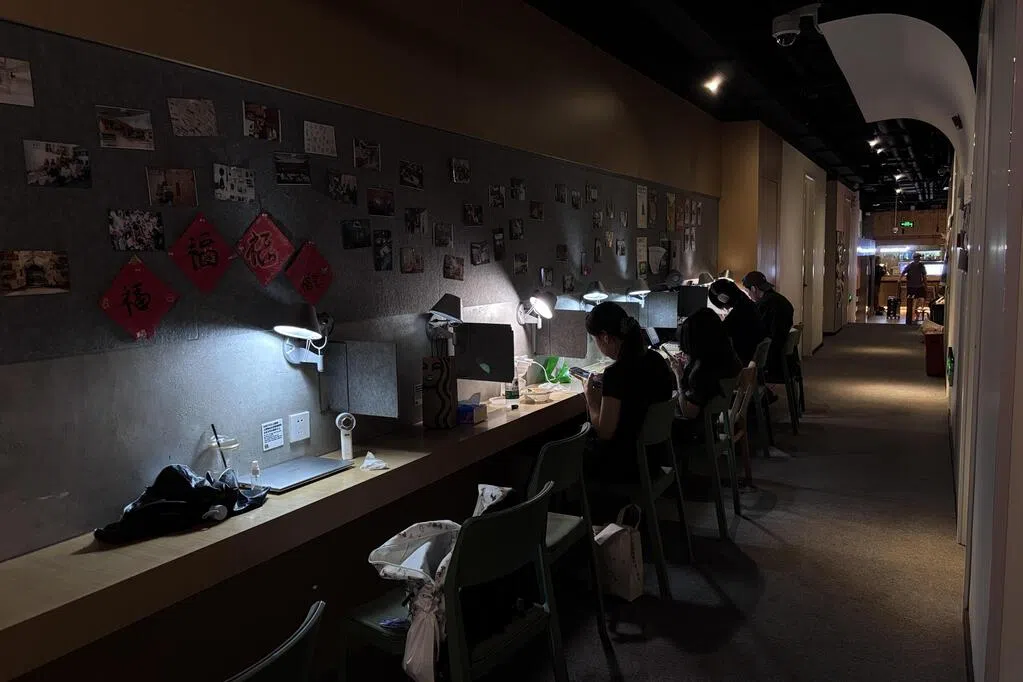

Communities built around “how to get out”

Eighteen-year-old Yong Haonan, currently studying abroad, has witnessed the trend from another angle. Since last April, he has been uploading videos explaining routes for ordinary people to work and migrate overseas, country by country. Within a few months, his account gained close to 30,000 followers.

He also created an online discussion community. Since launching it in September, total membership has approached 4,000. Members range from 16 to 35 years old, with most holding bachelor’s or associate degrees. Their top priority is obtaining first-hand information about overseas jobs and migration pathways.

To avoid attracting too much attention, Yong labels all groups as “language learning chat groups.” Members can also consult him one-on-one. Those seeking advice include everyone from Peking University undergraduates to IT workers in their 30s who were laid off and are considering going abroad to do plumbing or welding.

Unlike pricey migration agencies, Yong does not set a fixed price for consultations; people can tip voluntarily—sometimes a few yuan, sometimes 50 to 60. “My goal,” he said, “is to help a new generation of young Chinese—anxious about unemployment—go out.”

After going abroad: tougher competition, lower pay

At 28, Xiao Guan has already left. After sending out two to three hundred resumes last year without landing a suitable job in China, he changed strategy and secured a finance role posted to Indonesia within a month.

After a year in Indonesia, he was sent in October to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where conflict remains ongoing. Not long after arriving in Africa, he contracted malaria.

Xiao Guan said he chose Africa because the speed of saving money was “two to three times faster than in Indonesia.” He hopes to build enough “start-up capital” as quickly as possible to prepare for a next step: migrating to Germany.

But as more people compete for overseas opportunities, pay has dropped noticeably. “Ten years ago,” Xiao Guan said, “it wasn’t rare for Africa postings to pay over a million yuan a year. Now a bit over 10,000 yuan a month is enough to recruit people.”

As an HR professional, Xiao Bo is especially sensitive to how overseas pathways are changing. He can recite Australia’s state-by-state shortage occupation lists without checking. The once nearly permanent “three migration staples”—nursing, social work, and early childhood education—have shifted, he said: early childhood education has recently become oversupplied.

The narrowing channels once left him uncertain, but he ultimately decided he still had to leave. “Whether it will be better outside, I don’t know,” he said. “But can I accept the present? My answer is no.”

Beyond the economy: “non-economic” pressures

Economic outlook is only part of the story. In deeper conversations, multiple interviewees pointed to non-economic pressures as the forces making them feel they “must” leave.

For Xiao Bo, pessimism about employment mattered—but what truly broke him, he said, was the workplace environment at a central state-owned enterprise. Beyond attending ideological reporting sessions and Party meetings on rest days, he said the company also used a “Shenjian system” every week, connecting employees’ private phones by cable to scan their social media activity.

He said that during one inspection, he was found to have donated to Ukraine via cryptocurrency. He was required to write a self-criticism and was penalized by having more than 800 yuan deducted from his original 2,600-yuan monthly salary.

Xiao Bo initially assumed the matter was over. Later, colleagues warned him that it had become a “stain” on his record. He no longer felt treated as an “insider,” and he believed his chances of promotion had become minimal.

Analysis: what the migration impulse reveals

Xu Quan, a current-affairs commentator living in Taiwan, argued that Chinese people have historically been deeply attached to their home soil. When a population begins systematically planning life paths that involve “leaving the country,” he said, the most urgent question is what has gone wrong within society itself.

He noted that many young Chinese now seeking overseas work are willing to take labor-intensive jobs and relocate to non-traditional destinations such as South America and Africa—“which in itself shows extreme disappointment with current social conditions.”

Xu also said that a lack of upward mobility has long been discussed, but this year feels particularly stark. One reason, he argued, is the repeated “display of power and privilege” by vested interests, which strongly provokes ordinary people. He described a “closed loop” of resource control among privileged groups, leaving lower and middle strata struggling to gain access—and ultimately left with only “scraps.”

Fu Fangjian, an associate professor at Singapore Management University’s Lee Kong Chian School of Business, offered a broader view: feelings of powerlessness among young people are not unique to China, and American youth face severe job pressure as well. Macro-level reforms may be needed, he said, but for individuals, hardship is perennial—“so personal effort becomes even more important.”

In Fu’s view, going abroad is not necessarily a bad thing. If domestic competition is too intense, changing environments may help—“as the saying goes, people thrive when they move.” He added that Chinese trade reaches more than 190 countries, and young people who “go out” along with broader national globalization trends might “fight for a better tomorrow.”

As for whether life overseas will be better, Xu argued that those who choose to leave are not naïve about difficulties. “They’ve assessed the hardship,” he said, “and still choose to go—showing how determined they are.”

※新西兰全搜索©️版权所有

敬请关注新西兰全搜索New Zealand Review 在各大社交媒体平台的公众号。从这里读懂新西兰!️

了解 新西兰全搜索🔍 的更多信息

订阅后即可通过电子邮件收到最新文章。